Ichthyosis Vulgaris

Ichthyosis vulgaris is a skin condition resulting in dry, scaly skin, especially on the arms and legs. Its name is derived from the Greek word meaning “fish” and refers to the fish-like, scaly appearance of the skin that occurs.

Ichthyosis vulgaris can run in families (hereditary ichthyosis vulgaris), or it may develop later in life (acquired ichthyosis vulgaris). The hereditary type, also called congenital ichthyosis vulgaris, first appears in early childhood and accounts for more than 95% of cases of ichthyosis vulgaris. Hereditary ichthyosis vulgaris tends to improve after puberty. The acquired type usually develops in adulthood and results from an internal disease or the use of certain medications.

Who's At Risk?

Ichthyosis vulgaris is found in people of all races / ethnicities and sexes. Hereditary ichthyosis vulgaris is fairly common. As many as 1 in 250 children have hereditary ichthyosis vulgaris. In hereditary ichthyosis, usually at least one of the affected person’s parents had the same dry, scaly skin as a child.

Acquired ichthyosis vulgaris is rarer and is found almost exclusively in adults. It typically occurs in people on certain medications (eg, nicotinic acid, cimetidine, and clofazimine) or who have internal conditions such as:

- Poor nutrition.

- Infections, such as leprosy or HIV / AIDS.

- Glandular diseases, such as thyroid or parathyroid problems.

- Sarcoidosis.

- Cancer, such as lymphoma or multiple myeloma.

Ichthyosis vulgaris is more severe in those who live in cold, dry climates and who use harsh soaps or detergents.

Signs & Symptoms

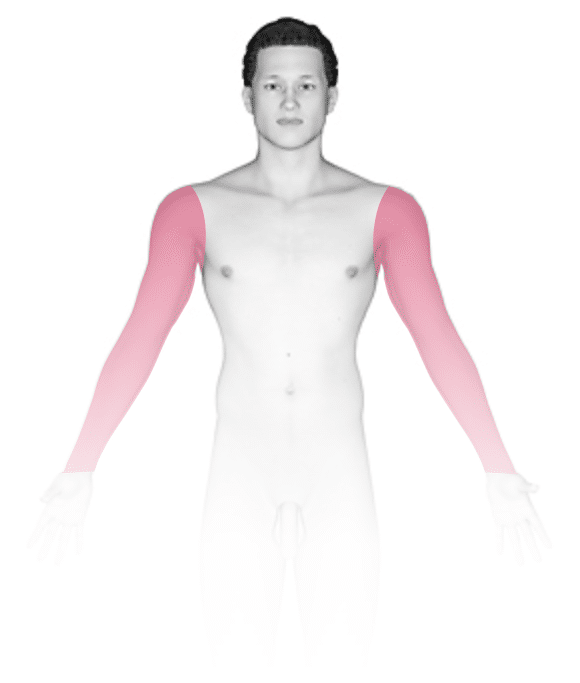

The scales of ichthyosis vulgaris range in size from 1-10 mm. The scales may be white, gray, or brown, with darker skin colors often having darker scales and lighter skin colors having lighter scales. The affected areas are usually itchy. The legs are typically affected more than the arms. The creases on the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet may crack during dry or cold weather. In more humid, warmer weather, the scaling will typically improve.

The most common locations for ichthyosis vulgaris include the:

- Fronts of the legs.

- Backs of the arms.

- Scalp.

- Back.

- Forehead and cheeks, especially in younger children.

Self-Care Guidelines

Ichthyosis vulgaris should improve by restoring moisture to the skin. Thick creams (eg, CeraVe Moisturizing Cream) and ointments (eg, Vaseline) are better moisturizers than lotions, and they should be applied just after bathing, while the skin is still moist, and at least one other time every day. The following over-the-counter products may be helpful:

- Preparations containing alpha-hydroxy acids such as glycolic acid or lactic acid (eg, AmLactin creams)

- Creams containing urea (eg, Pedinol Ureacin-20 cream)

- Over-the-counter cortisone cream (if the areas are itchy)

- Mild cleansers (eg, Cetaphil Gentle Skin Cleanser) instead of soaps

Any cracks in the skin should be treated immediately with an over-the-counter topical antibiotic ointment (eg, Neosporin) to help prevent infection.

Treatments

To treat the dry, scaly skin of ichthyosis vulgaris, the medical professional may recommend a topical cream or lotion containing:

- Prescription-strength alpha-hydroxy acid, salicylic acid, or urea.

- A retinoid medication such as tretinoin or tazarotene.

For more severe, stubborn ichthyosis vulgaris, oral treatments may include:

- Isotretinoin.

- Acitretin.

If acquired ichthyosis vulgaris is suspected, the medical professional will perform an examination and order tests to determine the underlying medical condition. They will also review your medication list to identify if you are taking anything that may have triggered its development. They will then try to treat the underlying condition or potentially discontinue the medication causing the ichthyosis, if feasible.

Visit Urgency

If you develop dry, scaly skin that is not improved by twice daily application of an over-the-counter moisturizer, see a medical professional for evaluation.

Trusted Links

References

Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018.

James WD, Elston D, Treat JR, Rosenbach MA. Andrew’s Diseases of the Skin. 13th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019.

Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2019.

Last modified on June 17th, 2024 at 3:16 pm

Not sure what to look for?

Try our new Rash and Skin Condition Finder