Impetigo

Impetigo is a common, contagious bacterial skin infection. It is usually only a minor problem, but sometimes complications may occur that require treatment. Impetigo often starts with a cut or break in the skin that allows bacteria to enter. Impetigo is usually caused by “staph” (Staphylococcus) or “strep” (Streptococcus) bacteria. Impetigo can be further classified into 2 types: bullous and nonbullous.

- Nonbullous impetigo accounts for most cases of impetigo and appears as tiny fluid-filled blisters that quickly develop into honey-colored, crusty lesions.

- Bullous impetigo appears as larger fluid-filled blisters. When these blisters break, they may leave a scab behind.

Who's At Risk?

Impetigo is very common in children because their immune systems are not fully developed. Impetigo affects up to 10% of children who come to a pediatric clinic. Children up to age 6 years are most likely to be infected.

People who live in warm, humid climates are also at risk. Insect bites, crowded living conditions, and poor skin cleansing increase the risk of infection. Impetigo may spread easily through schools, day-care centers, and nurseries. Participating in sports involving skin-to-skin contact, having a weak immune system, or having a chronic skin problem such as eczema can also increase your child’s risk of getting impetigo. It is very contagious and may spread easily with skin-to-skin contact, especially among household members.

Signs & Symptoms

Nonbullous impetigo:

- Nonbullous impetigo starts as tiny vesicles (small fluid-filled blisters) that break open quickly to form honey-colored, crusty papules (small, solid bumps) and plaques (raised areas of skin larger than a thumbnail). Sometimes the tiny vesicles are not seen at all as they break open very quickly.

- Sometimes the honey-colored crusts are surrounded by areas of inflammation. In lighter skin colors, the inflamed areas are often red. In darker skin colors, the redness may be subtle or may appear more purple or gray.

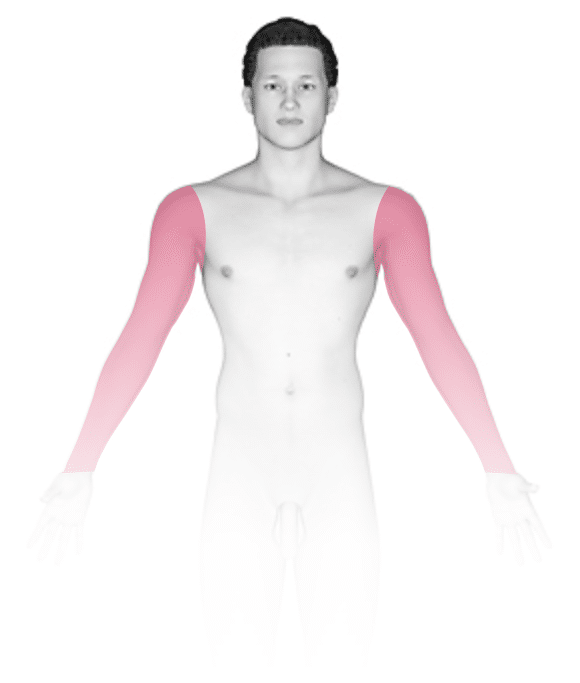

- The skin on the face, especially around the nose and mouth, and the arms and legs are commonly affected, but any area of skin can be affected.

- There may be some itching or swollen lymph nodes, but the person feels generally well (unless severe).

- Sometimes deeper pus-filled sores and scabs that leave scars occur.

Bullous impetigo:

- Painless vesicles (small blisters) that are about an inch or smaller occur that may contain yellow fluid and break easily, leaving a moist, red erosion (an area that appears sunken and missing its top layer of skin). The area will then quickly form a “varnish-like” crust.

- The trunk, arms, and legs are common locations for bullous impetigo.

- The person feels generally well (unless the impetigo is severe).

Self-Care Guidelines

Prevention is ideal and includes:

- Keeping the skin clean with soap and water.

- Treating cuts, scrapes, and insect bites by cleaning with soap and water and covering the area if possible.

For mild infection:

- Gently wash the area with a mild soap and water twice or more daily and cover with gauze or a nonstick dressing, if possible.

- Apply an over-the-counter antibiotic ointment after washing the skin 3-4 times daily. Wash your hands after application or wear gloves to apply the ointment.

- To remove crusts, soak in warm tap water or Burow’s solution for 15-20 minutes.

- Wash clothing, towels, and bedding regularly, and do not share these items with others. It is also helpful to have separate personal care items, such as soap, for the child.

- Your child should wash their hands frequently. Also keep the child’s nails trimmed, and encourage them to avoid touching the affected areas.

Treatments

If the above self-care measures are not adequately treating the infection, the child’s medical professional may prescribe:

- Topical antibiotics (eg, mupirocin or retapamulin), or

- Oral antibiotics (eg, cephalosporin, clindamycin, erythromycin, or other antibiotics).

If your child is prescribed antibiotics, be sure they take the full course.

Visit Urgency

See your child’s medical professional for any infection that does not improve with self-care measures. See the medical professional if there are more than a few skin lesions that are localized to one area of the body as this might need treatment with an oral antibiotic. Also seek medical care if your child has an infection and they develop a fever, or red and painful skin.

If your child is currently being treated for a skin infection that has not improved after 2-3 days of antibiotics, return to the child’s medical professional.

References

Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018.

James WD, Elston D, Treat JR, Rosenbach MA. Andrew’s Diseases of the Skin. 13th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019.

Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2019.

Paller A, Mancini A. Paller and Mancini: Hurwitz Clinical Pediatric Dermatology. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2022.

Last modified on June 17th, 2024 at 3:27 pm

Not sure what to look for?

Try our new Rash and Skin Condition Finder